Exploring a world of scares.

Why do we love horror? That’s the question I want to ask you today. Why, in a world of such beauty and wonder, do so many of us choose to sup from the well of fear? What does the gore, the psychological tension and the mysterious nature of the uncanny do to attract us so? From books to films, video games to escape rooms, being scared has been a selling point for the entertainment industry for centuries. Evidently, there is an insatiable lust for terror.

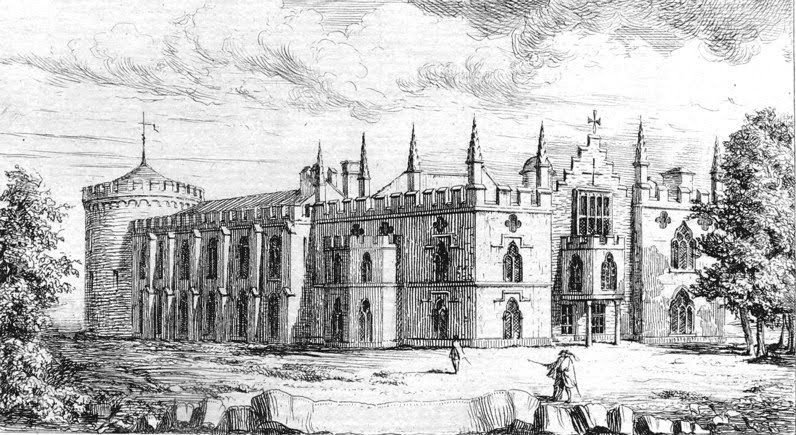

The beginning of the horror genre as we know it can be pinned down to two key dates in history, 1764 and 1960. Quite a dramatic difference in time does not separate our two moments in their importance. In 1764, Horace Walpole published The Castle of Otranto, widely regarded as the first novel in the Gothic genre of literature, paving the way for Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley to terrify and delight their audiences decades later. Then, in 1960, Alfred Hitchcock introduced the world to Psycho and the story of Norman Bates, elevating the horror genre above the Sci-Fi schlock of the 1950s and the low-budget cheese of the Universal era.

Both these dates are the equivalent of earthquakes in the horror genre. One popularised the reading of Gothic narratives in Europe in the eighteenth century and beyond and the other ushered in the time of the slasher film, spawning decades of homages, imitators and tributes. Michael Myers, Freddy Krueger, and Jason Vorhees all owe their popularity to Hitchcock’s creation. So what do both of these works have in common to tie them together in terms of their importance to the genre? Well, both Hitcock’s film and Walpole’s novella are artistic expressions that raise the question, why do we love horror?

Both the cinematic and literary horror genres have an unusually strong core, with a selection of books and films that can easily be described as an encapsulation of their respective genres. It is within these cores that we can find the themes and expressions that give horror its popularity.

First and foremost, most horror that finds popularity with a large audience does so because it manages to remain culturally relevant while eschewing realist tradition. An excellent example of this comes from a Gothic masterwork, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a work that is now 126 years old and yet remains as popular today as it did in 1897. The infamous Count Dracula may be a creature of the imagination, but what he represents is rooted firmly in reality, and the fears that follow him are just as salient today as they were in the nineteenth century.

Dracula, a powerful and wealthy count, is also a Romanian immigrant, moving West across Europe to fulfill his desires of establishing an empire in Britain. Dracula’s journey is similar to that of so many others, people both real and fictional, and while their dreams may be far less aspirational or diabolical than Dracula’s, the underlying western fear of an invasion of dangerous foreigners is contained within the microcosm of Dracula himself. This cultural anxiety has not abated since Stoker’s work was published and helps the story retain its popularity.

Similarly, as I write this in 2021 and Covid-19 continues to plague (pun intended) the international community, the notion of Dracula not only immigrating to England but also bringing with him a mysterious medical ailment in the form of vampirism that begins to affect local residents is eerily familiar to the beginnings of Covid in China and beyond. Vampirism has long been alleged to be a metaphor for viral infection and is perhaps second only to zombies in its ability to convey the public fear of uncontrollable sickness running rampant across the globe. Even throughout Stoker’s novel, Van Helsing analyses Lucy Westerna as a medical patient, with a disease that can be treated through scientific rigor and medicine. In Stoker’s time as well as our own, the disease was a threat not far from the public consciousness, the Plague, while less common was not entirely eradicated, and only two decades after Dracula, the Spanish Flu pandemic would take the lives of fifty million people worldwide. I would argue that Dracula has never been more apt a text for the early twenty-first century.

Yet horror does not have to be entirely dependent upon the context of society at large, many of the greatest horror films are ones that achieve universality through the simplicity of their themes and narratives. Moving to a cinematic example, I wrote earlier that Psycho popularised the slasher genre and was followed by a long line of imitators from Michael Myers in Halloween to Chucky in the Child’s Play series. While the thought of both of these psychotic killers is, on the most superficial level, unsettling, there is more to the fear of these characters than the sharpness of their knives or their lust for blood.

All of these killers share a set of attributes or similarities that bind them together in making them popular to audiences. Of course, there are differences, Child’s Play and A Nightmare on Elm Street are far more comfortable in trying to make us laugh and cry, whereas Friday the 13th and Halloween are more committed to straight-up terror. These killers are all connected by our universal fear of being hunted and stalked. Slasher villains pursue their victims with endless persistence, staying sure-footed while our characters fall, and getting up from every shot or stab. The idea of an immovable force, unrelenting and without empathy is terrifying, and what made Psycho such a seminal movie was that it removed any supernatural element from this terror. After Psycho, the evil killer could look as normal as you or I, they could be your best friend, your neighbor, or your husband; and they were not monsters conjured up in laboratories or living in Gothic castles, they were average joes who could strike at any moment. It is the chameleon-like ability of these antagonists that is so frightening, with Wes Craven’s Scream being an excellent contemporary example.

On the other hand, great horror can also revolve largely around characters. A perfect example of this can be found in Ridley Scott’s Alien and James Cameron’s Aliens. Yes, the design of the Xenomorphs is uncannily unsettling and the violence of their actions provides much gore. The setting too, of the Nostromo’s haunted house in space, is creepy and tinged with tension. But as the franchised progressed, particularly in the second and third films, much of the dramatic tension was dependent on the audience’s investment in Ellen Ripley, a one-time warrant officer and now a badass killer of aliens. While much of the suspense of the Alien series is built upon the aliens themselves and the innately isolated locales, the time invested in Ripley is what provides an even bigger portion of this underlying anxiety.

Ripley’s character development, across the first three films at least, is one of the most satisfying character arcs in film history. We get not only the scares of the Xenomorphs but also the pleasure of seeing a woman, so often written off and underestimated, rise up to become a soldier, a mother, and a survivor who is willing to sacrifice herself for the greater good. The Ripley who sacrifices herself at the end of Alien 3, content in the knowledge that she is ridding the galaxy of the alien threat for good (at least, until Alien: Resurrection) is a far cry from the rigid, run-of-the-mill lieutenant that we are introduced to at the beginning of Alien. Like any good story, horror must take a protagonist, remove them from equilibrium, and put them through the trials and tribulations that allow a new order to replace the old with a character changed in some dramatic fashion. This is something that Alien does excellently and manages to achieve while also providing a plethora of good scares along the way. It is an achievement that makes the horror genre so enjoyable, as we get to watch characters we love devleop and grow through a hardhsip that we share with them.

Aside from leaning on current cultural fears, engaging us with great characters, and playing on our most basic yet intense feelings of dread and anxiety, horror plays an important role in guiding our morality. By imagining the worst of humanity through the lens of horror, we escape making the mistakes of fiction in our own reality. To return briefly to a literary example, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is not only one of the most iconic tales in the Gothic canon, but it is also a wonderfully crafted morality tale. It is the story of man overreaching his boundaries and abusing the power of science and it has been firmly embedded into our consciousness for the past two centuries thanks to the power of Shelley’s storytelling ability. Raise any question about the morality of scientific progress or ethical boundaries and I guarantee that someone will bring up Shelley’s creation.

Frankenstein sees the young doctor of the same name, motivated by the death of his mother, seek to create new life from dead flesh and put the power of god into the hands of man. Naturally, he succeeds in his mission but, as things begin to go terribly wrong, he must accept the consequences of his actions and strive to write the wrongs of his own arrogance. Frankenstein, then, is not merely a story of a man-made monstrosity roaming the streets of Europe and terrorising its people, it is a story of mankind overreaching itself in the face of nature and unleashing the uncontrollable power of scientific discovery upon the world. Frankenstein’s creature could easily serve as a metaphor for the Atomic bomb, created over a century after the publication of Frankenstein but just like the creature, a deadly force born of scientific endeavor that is soon turned against the will of its creators. It is the cautinoary nature of this tale that makes it so engrossing, a what-if that relfects not only our cultural anxieties but also what makes us human in the face of nature and god.

At the beginning of this article, I asked the question why do I love horror and I think that the answer is this, it is probably the most versatile genre of film and fiction in the artistic sphere. Horror can fulfill an impressive variety of functions and is also flexible in its combinations with other genres. Horror can both delight and scare, sicken and side-split. It is this array of abilities that make the genre so attractive. Not only can films and books of this sort make us thankful for our own lives but showing us images and ideas so alien to our own worlds, but can also guide us to make change by making us aware of the dangers in our own worlds. Films like 28 Days Later and Dawn of the Dead (2004) are apt reminders to us all of the dangers inherent in disease, Jurassic Park, although more of a science-fiction film, scares us so because it demonstrates the awesome powers of science while films like It (2017) or Aliens scare us because of the lack of agency from those in authority who we would normally depend on to protect us.

Horror is such a wide-ranging and ever-evolving genre that it will persist for the foreseeable future. So long as humans exist, so will our sources of fear. Horror is our constant companion, a moral compass that can tell us what’s right and wrong with the world and it is also a timely reminder to make sure we know what lurks in the dark.